The Five Stages of Computing History, and What Could be Next for Quantum Computing (Part 2)

Power

I think that, along with speed, this is becoming one of the main focuses in recent years in the field of HPC. Ever since “Attention is all you need,” the AI boom has demanded immense computing power, and a significant amount of research has been delegated to developing less power-hungry ML models. Estimates have stated that there may be 10x more energy usage in a query to an LLM than Google Search. On top of that, Microsoft has recently announced plans to restart Three Mile Island, the site of a near-nuclear disaster in Pennsylvania, to power their AI development. A story that has particularly interested me is regarding the Colossus supercluster that Elon Musk’s XAI has built near Memphis. If the goals of reaching 100,000 H100 GPUs are true, then just that phase (one of three) will require over 500 MW of energy conservatively. The entire city of Memphis is maybe 4-6 times that (also conservatively estimated), resulting in slowdowns in the final steps of the datacenter design. This is ignoring the storage they would likely need for their facility, something that Generative AI is also greedy for.

So, now that it is clear that the second coming of the power squeeze is here in computing, let’s analyze what was done the last time this happened. NREL has a very interesting breakdown (see references section) which details some of the advancements that have, in many cases, made power an afterthought for new machines. Performance per watt has increased with GPUs and other energy-efficient processors outpacing dated tech, and the advent of widely utilized liquid cooling in data centers saves significant power from the thousands of fans required previously. Reviewing the Green500 list (from the people behind Top500) reveals more insights into this area of HPC, and shows promise in the efficiency of modern HPC centers.

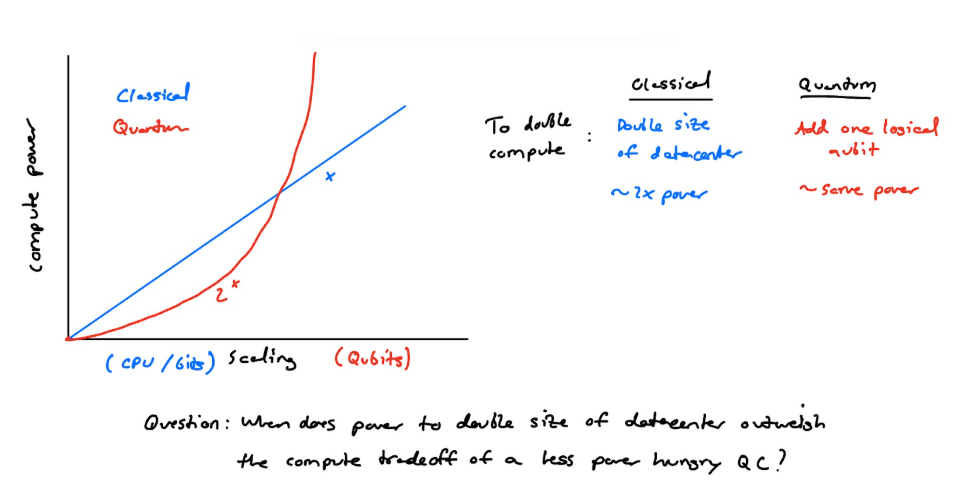

Since my specialization is quantum computing, this is a good point to mention where QC sits on the power scales. While it is widely touted as being more efficient than classical computing, the energy-intensive extreme cooling for most quantum computers in 2025 is a source of alarm. If we had a big enough quantum computer that had logical (high-quality) qubits, I would make a plot, but here is a replacement without numbers:

(Tablet) Napkin notes on Power and QC

Thus, while QC offers many tradeoffs regarding computational power, there is great optimism that electrical power will be minimized with these devices in large computations/workflows.

Reliability

This is a big one in both modern HPC and QC. Due to the newfound reliance we have on computers, including in the military, healthcare, critical infrastructure, and banking, we need to be positive that our computers will not break when they are needed most. Likewise, reliable results need to be produced from computers, especially when under stress, at all times. This is where HPC greatly outperforms QC, and likely will for decades to come. As I noted in the “correctness” section of the last post, quantum computers have serious problems related to noisy qubits and unstable initial conditions. If a critical process, such as a simulation of a patient’s organs in a medical situation, were required, quantum computers are inherently unlikely to produce the same result multiple times (unless explicitly designed and noise/error corrected). The greatest strength of quantum, its randomness, also presents a flaw that some fields, the medical field included, can not reconcile at this point. Imagine a quantum computer on a spaceship, such as the fabled SpaceX Starship, which is headed to Mars. Assuming it was a well-designed quantum computer with a reasonable number of logical qubits that it is saving space on the rocket, critical calculations would need to be run many times to ensure that said results are consistent. If landing the rocket, this could be a dealbreaker, where timing is critical and redundancy is key.

Security

While this last section is considered by the author to be the latest step in the field of HPC, with the growth of AI this has likely changed (as stated before). However, it is still relevant to mention the security of these systems, as well as their roles in cybersecurity, considering the widely connected world we live in in the 2020’s.

Most notably, quantum computers are considered the final nail in the coffin per se for RSA encryption. For those who are unfamiliar with the term, RSA encryption involves the use of two very large prime numbers being multiplied together and used as keys in a public key cryptosystem. Someone attempting to intercept this resultant large number would then be unable to factor the number, as it is a multiple of two primes, which have no non-prime factors. Because of this, it is widely used as a digital signature method, and banks, government services, and other highly critical infrastructure use RSA. Quantum computers, for reasons too long to explain in this shorter post, can leverage a method called Shor’s algorithm that makes this factorization method relatively trivial and can significantly speed up key decryption. While this is not a concern in 2025 since we would need hundreds of high quality qubits for the algorithm to work with the large numbers RSA uses, the NSA has expressed concern for save now, decrypt later attacks, where hackers may take data that is encrypted now and save it for a future date when quantum computers can be used to crack the key, and thus steal said information.

Another misconception with regards to quantum computers is that they are unhackable. This is not really true, and I am unsure where those I talk to hear it from. Quantum computers do not act fully independently of the classical realm, they are in fact controlled by relatively large classical computers themselves. These are no more secure than any other comparably sized computer we already have, and considering they could be used to sabotage or corrupt results, that is another important consideration.

However, the silver lining involves the development of new cryptographic methods using QC. While quantum key distribution, or QKD, features a number of flaws and is currently breakable, there is a new field exploring the use of quantum systems to generate highly random keys for cryptographic settings. Likewise, the field of post-quantum cryptography has evolved to adapt towards protecting industrial, government, and private assets from potential RSA collapses with stronger quantum computers, as well as steal now, decrypt later attacks.

References

AI brings soaring emissions for Google and Microsoft, a major contributor to climate change (NPR) Why Microsoft made a deal to help restart Three Mile Island (MIT Technology Review) XAI Colossus: The Elon Project (HPCwire) The Complexity of Noise (Goodreads) Data Center Energy Consumption Report (NREL)