Did Richard Feynman predict the future of computing?

Richard Feynman may be the most “worshipped” physicist of all time. I remember talking to a physics major I am friends with after the release of the Oppenheimer movie and asking what his favorite scene was, and he said he loved all of the scenes with Jack Quaid as young Feynman. For those who have not seen the movie, or missed his character completely, Feynman was a young scientist who contributed to the Manhattan Project, widely documented in many books he wrote himself, including “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!”: Adventures of a Curious Character and The Pleasure of Finding Things Out/The Meaning of It All, among others. Known as a jokester, he was one of the rare physicists who not only was highly gifted in the field, but was able to teach complex topics in a fascinating way.

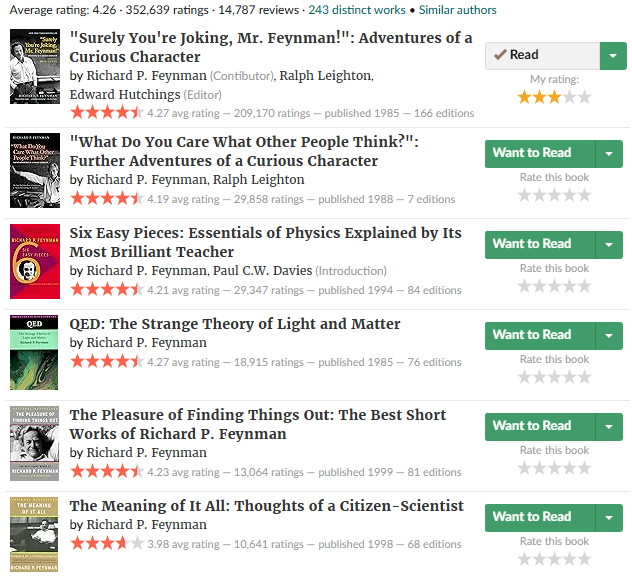

One thing that people have started to attribute (to varying degrees) to Richard Feynman is early optimism regarding the scaling of computing. In a talk at the Gakushuin University in Tokyo, Japan (source), some of his wit merges with his admittedly spot-on foresight to combine for an interesting read. As we dissect what he said, I encourage you to consider reading some of the books he wrote, collecting various speeches or thoughts such as this one. I have read three of his books now, and each was interesting and unique in its own way—just don’t become too obsessed like our physicist friends!

Richard Feynman's own Goodreads account

Speech Analysis

“…there is a great deal of work to try to develop smarter machines, machines which have a better relationship with the humans so that input and output can be made with less effort than the complex programming that’s necessary today. This goes under the name often of artificial intelligence, but I don’t like that name. Perhaps the unintelligent machines can do even better than the intelligent ones.”

The first ironic statement, considering this talk was given in 1985, when AI was a science fiction pipedream and couldn’t even beat a chess grandmaster yet. The term artificial intelligence was coined in 1956 by John McCarthy (Dartmouth) but had yet to be applied at a scale that offered any realistic comparison to its “unintelligent” contemporaries. Not the main reason I was interested in this chapter of his book, but for the first paragraph, it sure caught my attention!

“Another problem is the standardization of programming languages. There are too many languages today, and it would be a good idea to choose just one.”

I would be curious to see which Feynman would consider the best in 2025, or which he would choose. Engineering majors often debate this in my classes, with some of the common winners being Python (ease of use and range of applications), C (lower level but efficient), Java (supports a wide range of development), and Rust (these people never win the debates, just wanted to see if you were paying attention).

“I will talk about some technical possibilities for making machines. There will be three topics really. One is parallel processing machines which is something of the very near future, almost present, that is being developed now. Further in the future are questions of the energy consumption of machines which seems at the moment to be a limitation, but really isn’t. Finally I will talk about the size; it is always better to make the machines smaller, and the question is how much smaller is it still possible to make machines according to the laws of Nature, in principle.”

It is at this point that I became highly interested in the article, and I knew I had to write down my analysis and encourage discussion surrounding it. Each of these three topics has been extremely important in the last 40 years of computational research and development, and I dare say they are the top three most important topics, period.

“[Conventional computers have] effectively one central processor which is working very very fast and very hard while the whole memory sits out there like a vast filing cabinet of cards which are very rarely used. It is obvious that if there were more processors working at the same time we ought to be able to do calculations faster. But the problem is that someone who might be using one processor may be using some information from the memory that another one needs, and it gets very confusing. And so it has been said that it is very difficult to work many processors in parallel.”

This reference to a single CPU (or otherwise non-parallel) computer is one of the most basic I have ever seen, but it gets the job done. In computer architecture classes at my university, they spend a whole semester talking about the basics before parallelism beyond basic pipelining is explained. While it is important to know the basics, I find it ironic that, at least in the course I took in college, legitimate concerns scientists had 40 years ago were ignored in the pursuit of squishing dated content into a 12-15 week course. Feynman doesn’t even think it is worth his time to explain the benefits of parallel computing, stating that they are obvious, so I will move on here as well. Clearly, applications beyond Big Science may be significantly impacted by parallelism, and this was, even in 1985, a primary goal of HPC companies around the world, including in Japan.

“It is not possible to effectively use the old programs [with parallel computing]. They must be rewritten. That is a great disadvantage to most industrial applications and has met with considerable resistance.”

While this statement can be debated with tools like CUDA making parallelization easier than ever, reading this as I work on a GPU scheduling thesis has made me resonate with this idea even more. One of the main problems with modern GPU scheduling on a cluster is ensuring that a number of small jobs can share resources to the same scale as large jobs can. While CUDA may be optimal for massive workloads—hence NVIDIA’s stranglehold on AI—it has proven to be extremely difficult in my work to integrate elegantly with Kubernetes-based GPU scheduling platforms. Maybe in 40 more years this quote will be seen as a laughable joke to software engineers, but I would like to hope that I am not the only one struggling in 2025. On to the next topic…

“The second topic I want to talk about is energy loss in computers. The fact that they must be cooled is the limitation apparently to the largest computers; a good deal of the effect is spent in cooling machine. I would like to explain that this is simply a result of very poor engineering and is nothing fundamental at all.”

Summarizing this entire section in one sentence, Feynman comments on how many of the energy efficiency problems ailing computers in 1985 could be mitigated (partly) by reducing the size of a transistor, which is his third argument anyways. However, I still think this is an apt prediction of the current state of computing. A book I read recently cited five stages of computing: correctness, speed, power, reliability, and security. The author (whom I have forgotten, I will add as soon as I recall), stated that these were the five main design hurdles in HPC and computing in general over the last 50 years, in order. An argument could also be made that the order is not necessarily correct, as power and speed could be appended to the end of the list a second time each, resulting in seven stages of computing.

We have reached a point where there are considerable concerns about the energy usage of large-scale computing. Data centers supporting Grok and Microsoft AI are in the news for demanding obscene energy requirements, forcing them to build unique infrastructure beyond the use of a public grid for their AI demands. I can’t say first hand how much of a problem computing power usage was in the 1980s, but Feynman appears to be spot on predicting that physical scaling, while extremely helpful for power consumption, is not the only method that needs to be considered.

“So, my third topic is the size of computing elements and now I speak entirely theoretically. The first thing that you would worry about when things get very small is Brownian motion; everything is shaking and nothing stays in place, and how can you control the circuits then?”

This short line goes into a very interesting definition and theoretical explanation of reversible computing, which I encourage those of you who made it this far to read! However, to avoid copying the whole article, I am just attaching the quote above. This third and final section before the Q&A seems to reinforce his known belief that semiconductor technology will eventually reach a scale where considerations must be made related to quantum physics himself. He is also known for his 1959 lecture “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom,” where he discussed the possibility of manipulating individual atoms in computing, foreseeing the development of nanotechnology and extremely small-scale computing. Only in the 2020s have we reached a point where classical computing has met the quantum scale, and engineers have to finally go back to see what theoretical quantum physicists in the 1980s were saying!

One of the things that stood out to me here was the relationship with my field of interest, quantum computing. While quantum computing was barely being explored at that point, this combination of a talk on Brownian-based quantum error, reversible computing, and quantum scaling necessity seems to be no coincidence. It is notable that quantum computing is inherently reversible in concept (except for state measurement), allowing for all information in a computation to be maintained. While I am biased, it is also worth noting that the exponential speedup that separates quantum computing from classical and reversible computing was not mentioned in this talk, implying a greater focus on the latter.

Conclusion

Feynman’s insights from 1985 remain remarkably relevant today. His discussions on parallel processing, energy efficiency, and miniaturization of computing elements have all played central roles in the evolution of modern computing, holding strong in a rapidly evolving field. As we continue to push the boundaries of computation with HPC and QC, it is fascinating to see how his predictions and concerns still influence technological discourse. Perhaps the greatest lesson from his talk is that, while technology evolves, the fundamental challenges of computation remain strikingly consistent. Perhaps I need to watch Oppenheimer again and pay greater attention to the young Richard Feynman.